This conversation is part of a resource created by Fox Irving for Young Hearts, a programme produced by Heart of Glass. It is designed to create a dialogue amongst artists from the Women Working Class Network, exploring the challenges of provision, access and engagement around arts activities and experiences in relation to young women.

I listen as the women reflect on their own struggles to enter the arts. They offer advice, support and share personal stories, revealing the barriers facing many young working class women wishing for creative careers.

The barriers were varied, including practical concerns of financial security, and other concerns of how to build networks in the industry. But other obstacles were more intangible, indicating the emotional toll of attempting to join spaces and communities they felt were ‘not for them’.

The biggest barriers to a career in the arts lie in these intangible spaces. Crippling self-doubt and imposter syndrome can make it hard to persevere without strong support networks.

A one-way mirror

Marjorie H Morgan felt that for women of her background, the arts were only to be consumed, not to do. There wasn’t a space for the arts in young working class women’s lives. ‘It was like it was a one-way mirror.’ You could enjoy what others created, but not create yourself.

The lack of opportunities in the arts are part of a broader issue for working class young people. Being pushed into unwanted careers are other ways to make members of lower socio-economic groups lead passive lives. Just as poverty porn objectifies poverty, so does a lack of autonomy in working lives - as George Roberts describes, robbing people ‘of the vital components of all human life – agency, autonomy, and unlimited potential’.

In 2017, The UK’s Culture, Media and Sport Committee found that children were being '“actively deterred” by an education system that deprioritises the creative industries’ (Hall, 2018). In late 2021, the UK government cut funding for arts and creative subjects and are now actively considering limiting the number of students allowed to study creative and other ‘low earning’ subjects. All these measures particularly impact young people from working class backgrounds.

I just think of how often we are left in the cold as young people. Particularly if you don’t have the support or understanding of your family, your teachers, or your community to do what you want. The women spoke of being laughed at, dismissed, and actively discouraged from entering the arts by many of their teachers and career advisors.

They also spoke with fondness of that one teacher or arts worker who encouraged them to access arts spaces, to create, and, most importantly, who saw value in them, not only as future artists, but as human beings. The new government policy makes many fear it will have a devastating impact on future generations of working class young women.

Feeling like an Outsider

Another barrier of course, is the profession itself. Many of the women spoke of how they felt intentionally, or unintentionally, othered in cultural and educational spaces. They either felt judged by some of their peers as not good enough, as Cath Hoffman experienced, or felt that their educational institutions didn’t understand the lived realities of working class students, as Fox Irving reflected, who often have to juggle several jobs while undertaking a degree.

Kyra Cross warned against poverty porn and the lack of care many arts organisations provide for working class artists within their buildings. Marjorie H Morgan expressed her feeling of sorry that she was often only included as a ‘tick box’. There needs to be more understanding within arts organisations of the needs of artists that moves beyond tokenism, rather than what Sara Ahmed describes as the ‘Benneton method of diversity’ (Ahmed, 2021), which provides engagement and access to sell a brand, but fails to go beneath the surface.

Some of the women spoke of channelling a kind of dogged determination, or ‘bloody-mindedness’, to carve a career for themselves in the arts. But I was struck by how, for many of them, this came later in their lives. It was like, finally after working in other areas and learning from personal struggles, they decided to just go ahead and do it. Starting their careers at 30, 40, or older, also liberated them from defining themselves through one art form, or even one career.

Charlotte Cooper argued how this was not ‘a failure’ but a gift to her arts practice. By sharing their stories and their gateways into the arts, the women not only illustrate, but celebrate, the many paths into creative careers.

Seeing yourself in the arts

So, the question is, how do we foster environments that make young people from working class communities, particularly young women, see themselves in creative careers?

These conversations revealed why initiatives like the Young Hearts Programme and the Women Working Class Network are so important to offer exposure and guidance from role models who come from similar backgrounds; who look like, talk like, and understand the lived realities facing young women from working class backgrounds who want to enter the arts.

A 2018 study found that mentorship was vital to 'encourage young women from under-represented groups into male, white, and middle class dominated arts spaces (Hall, 2018).’ Marjorie H Morgan also emphasised the need for mentorship and support networks to help with the emotional stresses of being a working class artist.

Self-doubt can also be a crippling demon, and many working class women find it hard to stay confident when confronted with career setbacks. Encouraging young working class women to accept their whole selves through mentorship can aid in fostering career resilience and longevity.

To embrace how they speak, how they see the world, and what they have to give as artists, is essential to fully gain access to the creative workforce.

This is the way to change the arts.

As Charlotte Cooper says,

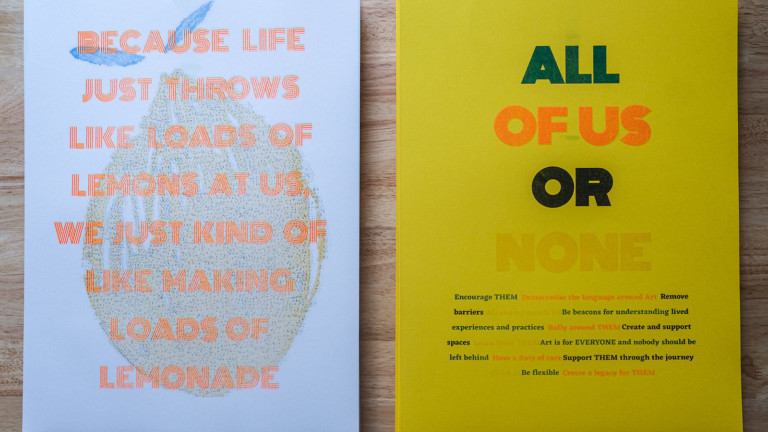

‘There should be a space for all of us, or none of us win’

Holly Maples is an academic, freelance theatre director, and actor. She has acted in and directed productions in the United States, Ireland and the United Kingdom. She is currently Senior Lecturer of Theatre and Director of Postgraduate Research at East 15 School of Acting, University of Essex.

Thought

Thought

Resource

Resource